First things first: a very happy new year to all of my readers! I hope 2017 will be filled with wonderful new culinary discoveries.

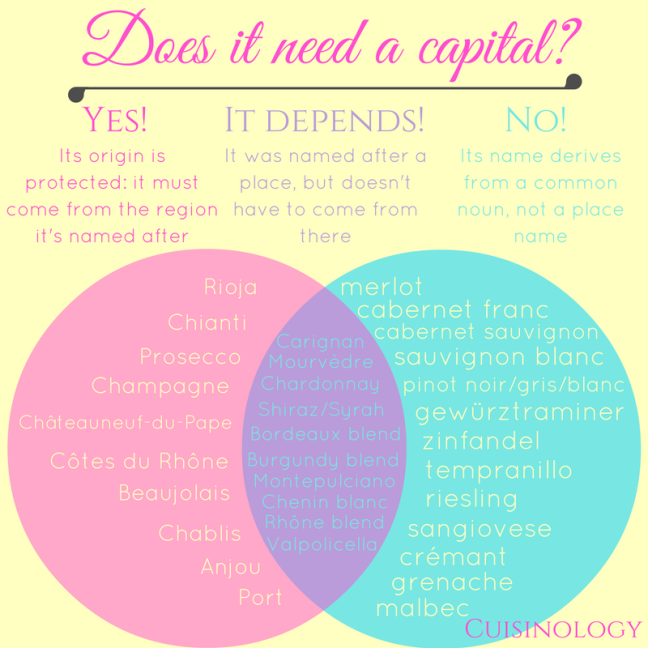

As promised, I’ve dug a little deeper into the etymologies of some of the most common grape varieties and wine blends to bring you this quick-reference capitalisation chart. This chart shows which wine grapes and styles should take a capital letter, according to the article by William Safire that I linked to in my last post. This is only one of many valid approaches to capitalisation in wine, and it’s by no means the simplest. But if its Google ranking and the prestige of the publication are anything to go by, it’s certainly one of the most popular approaches, so I’ve decided to expand on it with the chart and explanation below.

As you can see, most grape varieties and styles are named descriptively, not after a proper noun, and don’t need the upper case. Merlot, for example, is thought to come from the French merle, meaning blackbird: no reason to capitalise there. Sangiovese derives from the Italian for ‘the blood of Jove’ – and while Jove is a proper noun, blood (sangue) is not, so it’s sangiovese, not Sangiovese. Even when speaking of styles of wine such as crémant, the name comes from a mere description of the texture of the wine, and is no more deserving of a capital letter than the word ‘sparkling’ is.

Then there are the wines that are named after geographical locations. This is a slightly greyer area, and I determined three ways in which the name of a wine can coincide with a geographical region.

The first is when the wine itself is named after the same region where it was produced: this is the case for wines such as Champagne, Côtes du Rhône and Rioja. No wine can be described as Champagne unless it comes from Champagne, meaning that there is a clear connection with the proper noun and it should never be written in lower case.

Bordeaux, Burgundy and Rhône blends are also named after their origins, but these have since travelled the world and it’s possible to find bordeaux blends coming out of California. This is the second possible relationship between geography and wine: the word does refer to the wine region, but its meaning has expanded to refer more generally to the mixture of grape varieties (merlot, cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, petit verdot and malbec). For this reason, I’ve placed Bordeaux, Burgundy/Bourgogne and Rhône in the centre column; unless the wine in question really does come from its namesake, it’s up to you whether to capitalise or not.

The third category is when a grape is named after the region it comes from, but wines made from this grape can be produced anywhere in the world: this is true of the grapes shiraz, chardonnay and valpolicella. Shiraz, for example, is the name of a town in Iran, and the grape was named after this town (the variant Syrah is simply the French name for the same town). But for the most part, when we refer to a wine as ‘shiraz’, we don’t mean that it came from Shiraz – we mean that it is made from the shiraz grape. In this case, I would argue that it should take a lower case letter, unless it happens to be an Iranian shiraz from Shiraz…

A bit of a minefield then, that’s for sure. It’s worth noting, though, that neither the Oxford English Dictionary nor the Chicago Style Manual has published any hard and fast rules on how to approach capitalisation in wine. Perhaps one day they will, but until then, it seems every publication and every writer does it differently. This approach makes the most sense to me, but you do you: as long as you are consistent and can justify your use of capitals, I’m sure the grammar police (or Grammar Police?) will leave you in peace. 😉

4 Jan 2017: Edited to correct the origin of Chianti wine (it is named after the region and should always be capitalised) and to clarify the aim of this article: to explain one possible approach to capitalisation in wine, not to maintain that it is the only correct one.

Nice piece Megan. Cheers 🙂

LikeLike